Protecting property rights in a digital world

This document is authored and periodically updated by Russell McOrmond. Please send me any comments you may have.

Summary

Copyright is often discussed as needing a balance between the interests of copyright owners (sometimes creators) on one hand, and audiences on the other. With Paracopyright you have two additional interests to balance, with all 4 interests needing to be understood as owners worthy of respect and protection under the law.

Paracopyright is a term that refers to an umbrella of legal protections above and beyond traditional copyright for specific uses of technology. In Bill C-11 the term "technological protection measures" (TPMs) is used.

Digitally-encoded content can’t make decisions any more than a paperback book is capable of reading itself out loud. If there are any rules to be enforced, including whether a work can be copied, they are encoded in software which runs on some device. It is science fiction to believe that a technology applied to content alone can "make decisions."

Understanding the real-world market and human rights impacts of these technologies requires understanding all the components, and including the motivations of software authors (including the anti-competitive interests of DRM vendors) as well as the fundamental (but all too often ignored) rights of the owners of the devices.

Unless we are fully aware of all four classes of owners, we risk inadvertently supporting and/or enacting laws which will circumvent rather than protect our property rights.

I first introduced these ideas in 2006 at the Ottawa Linux Symposium, in Montreal for the FACIL August monthly meeting, and then at CopyCamp.

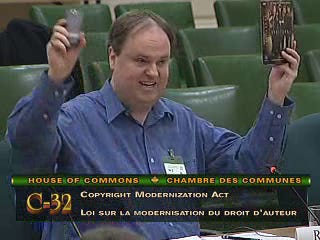

I had the opportunity to give this presentation in front of the Bill C-32 special legislative committee. The music CD had been upgraded to a DVD set of Sanctuary season 2, and the CD player had been upgraded to my Google Nexus 1 "phone".

If you want an answer to the question, "If you don't like locked content or non-owner locked devices, then just don't buy them", please see: When consumer choice is not enough: Dishonest Relationship Misinformation (DRM) or Why Heritage Minister James Moore is wrong on Bill C-11 "technological protection measures" (TPMs)

Note: The above image was taken from a handout I did (OpenDocument, PDF) for a presentation to a lawyer.

I made a relatively short (9 minutes, 22 seconds) audio recording (FLAC) to explain the handout. Please use this as you wish, with attribution.

Protecting property rights in a digital world

The dictionary defines Capitalism as, "An economic system in which the means of production and distribution are privately or corporately owned and development is proportionate to the accumulation and reinvestment of profits gained in a free market."

We are told that Canada and the United States are capitalist countries, but what does this mean for the digital technology used in the new economy? Many bills and proposals from capitalist governments suggest there is confusion on what private ownership of the means of production and distribution in a digital economy would mean.

There are other reasons to protect property rights in digital technology beyond economic arguments. The basic protection of communication rights, which are protected in the United Nations Declaration of human rights as well as the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms, also requires that the means of production, distribution and access of digital content be owned by individual citizens.

Understanding the pieces of the puzzle

I will use some some props to help us explore these ideas. Imagine that in my hands I am holding 4 things

(Picture me holding up a music CD and a portable CD player).

Two of these things are tangibles which you can see, and two of them are intangibles which you can't see, but are present and important. With each of these things you need to ask yourself who owns them, and how governments should be expected to protect the rights of these owners.

A) The digitally encoded music

The person or entity which holds the copyright on the content is all too often the only "owner" which is remembered in digital copyright discussions. While it is important that we protect the rights of copyright holders, this is only one of potentially 4 different owners we need to be concerned with.

B) The physical CD.

The person who purchases the CD has some property rights to the CD. No matter what the contents are of the CD the owner of the CD has the right to destroy the CD, but other rights are dependent on what is contained on the CD.

For recorded music the owner also has the right to resell and loan the CD as they would any other tangible property. Every Canadian has also been granted the right to make private copies of the contents of the CD.

Audiences, as well as librarians and archivists, need to think about how the relationship is different if there is no physical medium.

C) The CD player.

In this case it is hardware used to access the music on the CD, but this represents any hardware used to produce, distribute or access content. It could be portable or home entertainment equipment, a camcorder or digital camera, or your computer.

The owner should have the protected right to control what they own, just as they could with any other tangible property. If the purpose which they wish to use their property for is unlawful, this is an issue that should be handled in the courts and not attempted to be enforced by limits manufactured into the hardware, or by allowing someone other than the owner to have remote-control over the hardware.

D) The software executed on the CD player.

While software has a copyright holder like the music on the CD, is is more important to think of software as the set of rules which the CD player obeys. Within the physical limits of the hardware, such as its processing power, everything else is controlled in software: what file formats the CD player can access, and what happens when you hit the fast-forward button. Who authors these rules, and whose interests are protected by these rules, are critical to understanding whether these rules will honour the rights of the owner of the hardware, or in some way circumvent their rights.

Multiple Rightsholders

While the example of a CD player is one where the owner of the device is the audience of the content, the same components exist on the production side as well. The simplest situation for a photographer is when they own their own camera and blank media, and thus are the owners of the hardware, owners of the storage media and the copyright holder.

Whether the hardware device is being used by a creator or a user of creative works, the property rights of the owners of this hardware must be equally protected. The law should never suggest that the hardware property rights of creators should be protected, but not of audiences, given there is no way for technology to ever know the difference between audiences and creators who are building their own creativity on top of past creativity.

Whether we are talking about music delivered to music fans, or a photographer using a camera to take a picture, at least three of these things are always present: the hardware device, the software controlling the device, and the copyright holder. Increasingly digital content is communicated between the producer and the user through means that do not involve any physical media, such as digital downloads, which would not include the property rights associated with the owner of that physical media.

One of the rights that the owner of hardware must have is the right to choose the software that their hardware obeys. This may not seem critical for a CD player which is only expected to do limited things, but should be obvious for things we think of computers. The right for the owner to choose software, possibly to even author software themselves if they have the skills, is the only way to ensure that the hardware is obeying the instructions of its owner rather than someone who might be attacking their property.

What is possible?

Some of the confusion in this debate comes from misunderstandings about what is even possible to do. The most important question to ask is what is possible to do if the only thing we were manipulating is the digitally encoded content and the manufacturing of the medium it was stored on. These are two things which are directly controlled by a copyright holder.

It is possible to use cryptography to encrypt the content such that a digital key is needed to access it. This is the technique most often discussed, and why the concept of "digital locks" and "digital keys" come up often in discussions.

Content can also be digitally signed such that the recipient can verify the authenticity and integrity of the content. Digital watermarks can be used so that the copyright holder could automatically detect the origins of the file if it were unlawfully distributed.

The file format and/or the medium the file is stored on can also have deliberate defects introduced.

An example is Macrovision which introduced defects in the video signal output from a VCR that would be misinterpreted by a second VCR that accepted that video signal as an input. This would cause extremely poor quality copies, unless devices such as a time base corrector (TBC) were inserted between the two VCRs to correct defects.

A similar use of media defects is used with many audio-CD "copy control" techniques, which aim to play correctly on common home stereo equipment but where the defects will cause the CD to not be able to be played in a computer's CD player.

There are obvious problems with this scheme, which is that these manufactured defects depend on very specific behaviour of specific playback and recording equipment. Failures of the system will be common as people use older or newer equipment than those tested for the scheme. It can fail by disallowing a legal owner of the media to access the content, and it can also fail by not disallowing infringement which is its claimed intent.

Manufactured media defects can interact poorly with other media defects that happen over time, such as scratches on a CD, which often mean that the media is far more vulnerable to damage than they might otherwise have been if the manufactured defects had not been introduced. Newer playback devices designed to better handle defects may automatically correct the manufactured defects as well, acting as if the "copy control" never existed.

What is not possible?

One thing people think is possible that can not be done is for the digital content plus the media to somehow "make decisions". Content is passive, and while it can be encoded in such a way to deny access to those without the right keys, it is no more capable of making decisions than a paperback book is capable of reading itself out loud.

Many people who are critical of technical measures applied by copyright holders often suggest that these restrictions should expire when copyright expires. The term of copyright is often quite hard to determine, and with changes in legislation and the problem of it being tied to the death of the author (someone who is not always easy to determine) means the copyright expiry date can change over time. This means that it is not practically possible to encode a copyright expiry date in the content.

Beyond these major deficiencies in copyright law, being able to access the content is a "yes" or "no" type of question. If the content is encrypted you will have access to the right decryption keys or you will not, and the content cannot "decrypt itself" at some future date. For media defects your playback device can either access it or it can not, with the far greater likelihood that the media itself will have become impossible to read decades before the copyright expires.

It is possible for the law to specifically allow the circumvention of a digital lock, or the public publishing of decryption keys of content that has entered the public domain. This is one of many reasons why it is critically important to tie laws that disallow circumvention of a technical measure applied to content to acts which would be infringing.

Conflicts between hardware owners and new creators vs. past copyright holders

While reading the past section you will likely be thinking of various companies such as Apple and Microsoft who have promised that their technologies can do more than what I have indicated is possible. It turns out that these additional techniques aren't accomplished by applying a technical measure to the content that is owned by the copyright holder, or to the media that is authorized to be manufactured by the copyright holder. These are applications of technical measures being applied to devices that are owned by persons other than the copyright holder.

The concept is an extremely controversial one. The theory is that if new technologies can be abused to disrupt the business models of the incumbent content industry, then private citizens should not be allowed to own and/or control these new technologies. Manufacturers are applying technical measures to devices they sell which treat the owners of these devices as attackers of these devices, theoretically allowing the manufacturers to retain control these devices. Governments are seeking to pass laws which disallow features to be implemented in hardware which would in any way disrupt the business models of incumbents in the content industry.

This is a clear example of "Robbing Peter to Pay Paul". Private citizens and the next generation of creators are denied the the right to own, control and benefit from new technologies they could use to produce, distribute and access their own content. This is being done in order to protect the special interests of incumbent industries that rely on business models enabled by older technology and/or disrupted by new technology.

Language problems

We have been having problems with the language used in this debate. One common acronym that has been used is DRM which can stand for "Digital Rights Management" or "Digital Restrictions Management", depending on whether you believe what is being regulated by this technology relate to things which are rights.

The problem is that the term DRM is being used to describe a wide variety of things which have little in common.

The combination of digital content encoded such that it can only be played on "authorized players", with the only authorized players being those where the owner of the hardware is assumed to be the "attacker" of that hardware. Example: DVD CSS, Apple's FairPlay, Microsoft's Windows Media Digital Rights Management.

The use of technical measures by the owner of the hardware to protect them from unauthorized access to the computer, or unauthorized access to files or other data. Examples: computer firewalls, IP Security, SSL encryption used by secure websites, encrypted and/or signed emails, PGP/GPG, ...

Technological mandates from governments where manufacturers of devices capable of recording must "detect" if they are recording copyrighted works and "disable themselves" ("Closing the Analog-hole"), or where manufacturers of radio/television receivers must cripple them such that it isn't possible to record from them ("Broadcast Flags").

The first type is highly controversial as it "Robs Peter to Pay Paul" in that it revokes the property rights of the owners of hardware, and/or ties the ability to access digital content to specific brands of players. Both of these aspects should be understood as illegal, one as a circumvention of tangible property rights and the second as a violation of anti-trust/competition law.

The second type is not controversial, and is something critically important to protect the owner of a computer from third party attackers. Those who are lobbying for the first type deliberately confuse people into thinking that they are talking about the second even though one circumvents the rights of the device owner while the other protects it.

The third type is as controversial as the first, and would disallow the owners of this hardware to install their own software, or disable them from exercising rights granted to them under copyright law (Fair Use in the USA, Fair Dealings in Canada, etc) or other laws. It would make modern software marketplaces such as Free/Libre and Open Source (FLOSS) effectively illegal, as any device that can receive digital signals or record would not be allowed to run software which the owner (or their agent) could modify.

When people explain cryptography they often call them digital locks. The important question to always ask is: is the owner the person who has all the keys such that they can decide who to let in and who to keep out, or does someone else have the keys and will use them to decide when and under what conditions the owner will be allowed in. In the above 3 scenarios only the second protects the rights of the owner, while the other two directly attack the rights of the owner.

If you want to visually understand this question of who keeps the keys to the digital locks, and who is being locked out by these keys, please watch LAFKON's video about "Trusted Computing".

What about new business models?

There are a number of vendors of content and devices which want to offer new business models. You hear this all the time in policy discussions suggesting that, "wouldn't it be fair if we could offer you only the features that you need for a lower price"? The short answer is that while some aspects of the business models they want to explore may have some legitimacy, that the details of what they are asking for isn't fair.

These new business models aren't actually all that new. There are many business models that allow people limited use of something that they are not intended to own, possibly even use for a limited amount of time. We are all familiar with renting rather than purchasing a home, where the person living in the home is not the person who owns the home.

Separating the concept of rental and purchasing is not nit-picking. The legal regimes that regulate rental and ownership are entirely different, with each party in this transaction having rights and responsibilities that are fairly well understood by both the legal community and the general public. If a vendor, whether of information technology or a home, wants to offer you something less than full property rights and yet uses language that implies you are "purchasing", they are effectively trying to pull a fast one on you (and the legal system). They are trying to set up a business relationship where they receive the legal and other benefits of both a rental and a selling relationship, ensuring that you do not receive the benefits of either type of relationship.

The question of legal protection for TPMs needs to be analysed separate from the wide variety of business arrangements that are possible. TPMs should be legally protected when used to protect the rights of the owner of the hardware, and legally prohibited when used to circumvent the rights of the owner. In the case of a purchasing transaction, this means that the TPMs should be protecting the rights of the new owner, and the manufacturer or any other previous owner should no longer have any control over the hardware that is not authorized by the new owner. In the case of a rental transaction, this means the TPMs should be protecting the rights of the rental company who owns the hardware, with the person renting the hardware being prohibited from tampering with the hardware and software in ways not authorized by the owner.

This legal protection of ownership rights must have the same limits that already exist in law, meaning that when the owner rents to some other person that the protections that exist of renters of other property still apply to renters of information technology. Being the owner of the technology does not mean that privacy and other legislation protecting the renter is waived, nor does it allow you to circumvent competition and other laws which protect the economy as a whole. There is nothing so special about business models in the content industries or information technology that should suggest that governments should waive existing legal protections that exist in the rest of the economy.

Some additional example problems

While many of the arguments are economic, there are far more critical problems to consider. Some believe it is justifiable to allow third parties to control technology such as a VCR. I would hope that this would not extend to technologies that are more critical to ones life. We are moving into a world where digitally controlled prosthetic limbs are becoming a reality, and it is not so far off when ICT will be critical for hearing, eyesight and other such senses. It should be clear that the owner of these technologies, the person whose these technologies are integrated with, should be in control of them -- no matter what theoretical or real economic harm to a third party could result. (See article: Why personal ownership and control over IT is critical for our future!)

Camcorder in front of television: manufacturers' of recording devices such as camcorders, cameras and audio recorders could be mandated by governments to detect watermarks and automatically disable themselves, meaning that you could not photograph your child's first steps if it happens to be in front of a television set. This mandate is often discussed under the title of "Closing the Analog Hole" or "Plugging the A-Hole". As with all other technical measures, there is no way to create technology that can differentiate between legitimate creativity and copyright infringement.

Platform monopolies: while we have competition law to protect the economy from monopolies, DRM is being used by companies like Apple to insert themselves as a platform monopoly between creators and their audiences. This can revoke any remaining rights from creators and their audiences if the platform monopoly is allowed to become large enough to dictate policy to anyone who can access the platform (IE: who wish to use it to publish their works, or use it to access the works of others)

Region encoding / price differentiation: While this may be beneficial to the platform or other monopoly, it is something that is largely prohibited in law as the creation of the monopoly is itself harmful to the economy. Unfortunately in Canada the region encoding of DVD's has been hard to get the competition bureau interested in as we are in "region 1" along with Hollywood, with bureaucrats largely ignoring the fact that there are movies released first or only into other markets that are of interest to Canadians.

DRM being used for purposes entirely outside of copyright law, and/or things that would otherwise be considered unlawful. Example: circumvent trade and competition law, allowing incumbent monopolies to use price differentiation or protect platform monopolies (See: Freedom to Tinker: DRM Wars: The Next Generation )

There are more problems than can possibly be enumerated in a single article. Michael Geist offered a series in August and September of 2006 called 30 days of DRM where he spoke about more than 30 different problems. The Free Software Foundation also host a project called Defective By Design which documents additional problems.